Most professional people write for a living; they just don't consider themselves writers. They have to distil complex and frequently indistinct, sometimes contradictory, information into a credible, coherent story that sells a product, persuades a client or a boss, garners the funds and motivates the people necessary to accomplish a project, delays a creditor; the list of purposes for business writing is endless.

Business/Technical/Professonal writing is transactional; your words are supposed to do something for someone in particular: inform, explain, persuade, clarify, motivate. You aren't writing a novel. You aren't writing an academic essay either. The ideal business communication contains a 1::0 information to noise ratio, all information, no noise, no ornaments, no ego. Use the fewest words necessary. The subject matter, the content, is everything. That does not mean, however, the grammar and spelling don't count. The details count more than you might expect. Busy people look for any reason to move on, and a spelling mistake might make them hit delete, to say nothing of a badly written sentence or a foolish assumption. Even typos can be expensive.

Really good communicators draft and revise and proofread tirelessly in private so when they make their writing public, it speaks for itself. A full 3/4s of your time writing should be self-directed, for your eyes only, notes, diagrams, flow charts, graphs, drafts, revisions. The more work you do, the less work your readers have to do, and saving your readers time and effort are mission critical. You want to give your readers a spoonful of honey, not a wagonload of pollen.

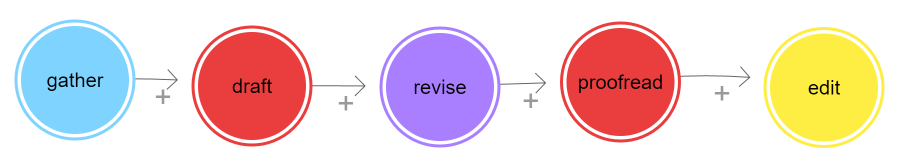

People who teach writing often talk about "the writing process", which consists of gathering, drafting, revising, proofreading, and editing. Talking about writing this way leaves people with the mistaken belief that writing is a linear set of discrete tasks, like that depicted left. Writing is in fact iterative; the tasks blend and recur. Click on the image below on the right to visualize "iterative".

Nevertheless, because writing is so difficult and there are so many things to learn and practice, having a parts lists and a schematic, as it were, may help you refine your current writing practices.

I will give you the view from 36,000 feet first and then some concrete advice and opportunities to practice.

Information gathering is the process of objectively gathering as much content from as many different sources as you can to create an archive. The content you gather can take many forms: words, images, storyboards, audio files, data sets, diagrams, graphs, video clips. During the gathering stage you don't yet know what you want to say, so you can't yet determine the value or even the relevance of anything you put into your archive. The bigger your archive, the better. Build with expansion in mind. Ideally you will get to reuse parts of it for subsequent projects.

For information gathering you might find a program like Evernote or OneNote or Keep helpful because you can keep any kind of digital file in these programs and you can make tags and keywords and otherwise search your information as it grows beyond what you can keep in your own memory.

Most people enjoy information gathering, especially if the subject interests them, and they don't yet have any fixed ideas about it. If you start archiving information with a fixed idea in mind, any information that supports your prior beliefs will please you. But anything that doesn't conform will be a source of dissonance, and you, like me and everyone else, will tend to discount or deny or even entirely overlook any evidence to the contrary. This tendency to seek confirmation and avoid disconfirmation is called the confirmation bias and it is hard to overcome. Try to gather impartially. If you don't, your archive will be misleading.

Data can be acquired in different ways, resulting in different kinds of evidence, each with its own characteristics, issues, and values.

Here's a cheat sheet for thinking your way through your data:

Eventually you will need to shift your focus from gathering to drafting. You need to resist the urge to remain forever in the archival stage, but you also need to avoid sealing the vault. A late arriving piece of information or data may be critical, and it may be merely distracting. So rather than thinking of gathering and drafting as exclusive activities, simply shift the bulk of your attention to one while leaving enough energy for the other.

Drafting (aka thinking with a keyboard or pen) is the initial stages of writing up what you think your archive says. Some people start drafting by writing a detailed outline of the subject, switching back and forth between overview and detail view as ideas occur to them. Some people just start writing and then create an outline after they have a clearer sense of what their data says. You should schedule multiple drafting sessions because not everything will occur to you at once. Some ideas surface slowly. Many people re-read before bed and then revise first thing in the morning. Sleeping on it helps.

Diligent researchers sit down to proofread a section and find themselves revising a sentence only to get up hours later having re-written the whole thing. No pain, no gain. Trying to figure out how best to say something often leads to clarity about what you are actually trying to say. Proofreading helps you clarify your ideas and clarity leads to effective revision.

Revising is about sorting and organizing ideas in order to clarify what the data says; refining definitions; making careful distinctions among similar things, vivid distinctions among dissimilar things, establishing important connections through correct transitions; responding to anticipated objections; finding and eliminating gaps in the logic, unwarranted assumptions, over-generalizations, needless repetitions. Through revising you might discover that you have more drafting to do, that you haven't yet said everything or that in the process of clarifying the meaning of a key idea you realize you wrote other parts with a fuzzy understanding and now you have to re-write those sections and then look for other places where the fuzziness persists or may have lead to other fuzzy thoughts. Just as proofreading leads to more revising, more revising leads back to the archive and then more drafting. Then the cycle resets.

You need to develop your own way of writing and refine it over time. If you are like most college students, you already have a writing process and that consists of drafting and proofreading performed in a single session, often the night before an assignment is due. Your mantra is: "The best grade for the least possible effort." Efficiency when it comes to learning is actually suboptimal. The real value of writing is to refine your understanding of things and to question your assumptions and beliefs. You can't learn deeply in a single session any more than you can get fit by working your biceps for fifteen minutes.